Eritrea: A Nation Forged Through Struggle

By : – Bana Negusse

Located in the volatile Horn of Africa and blessed with a long, unspoiled Red Sea coastline, Eritrea is a nation with a rich, complex, and often turbulent history marked by successive external rules and occupation. After waging one of Africa’s most prolonged and most devastating liberation wars, Eritrea secured independence from Ethiopia in 1991. This multipart series sheds light on the country’s decades-long struggle for freedom and identity.

Origins at the dawn of humanity

Archaeological discoveries in Eritrea’s Danakil Depression – especially in Buya – have revealed hominid remains dating back approximately 1.5 to 2 million years, placing the region at the very roots of human history. Prehistoric sites scattered across the country feature rock art, ancient tools, and artifacts, while evidence of early agriculture and animal domestication dates back to around 5000 BCE.

Moreover, many scholars identify Eritrea as the most likely site of the fabled Land of Punt – an ancient trading partner of the Egyptians, which further emphasizes its significance in early human civilization.

Before the colonial era, various parts of present-day Eritrea experienced intermittent invasions and occupations by foreign powers. Egyptians and Ottoman Turks held sway over coastal cities like Massawa and swathes of the lowlands. Meanwhile, rival warriors, feudal lords, and monarchs from surrounding regions launched periodic, short-lived incursions, often met with fierce resistance.

Italian colonization and the rise of modern infrastructure

In the late 19th century, Italy began acquiring coastal territory and gradually extended its reach inland, seeking to establish a settler colonial state. With tacit British support – motivated by geopolitical rivalry with the French – Italy formally declared Eritrea its “colonia primogenita” (firstborn colony) on January 1, 1890. Massawa was named the capital before Asmara assumed the role in 1897, which it retains today.

Over the next 50 years, Eritrea remained under Italian rule. Eritreans endured systemic exploitation, racial segregation, forced labor, and land dispossession. Education was restricted to basic levels, meant only to serve Italian needs. Eritreans were barred from many parts of Asmara and suffered under colonial apartheid policies.

Yet amid this oppression, the colonial period saw significant infrastructure development and modernization. The period saw the building of ports, railways, airports, hospitals, factories, and communications networks, positioning Eritrea as one of the most industrialized regions in Africa at the time. The Teleferica Massaua-Asmara – a 75-kilometer aerial tramway – was the world’s longest cableway when constructed.

In an enlightening 2006 article, the Eritrean scholar Rahel Almedom wrote how, after assuming control of Eritrea following Italian colonization, “the British had inherited a thriving local economy,” while Brigadier Stephen H. Longrigg, a civilian who from 1942 to 1944 served as chief administrator of the British Military Administration (BMA) in Eritrea, described the country as “highly developed,” and noted that it had, “superb roads, a railway, airports, a European city as its capital, [and] public services up to European standards.”

Additionally, as noted by two Westerners who lived in Eritrea, “In 1935, Asmara, which was made the Eritrean capital in 1897, was the most modern and progressive city in Italian East Africa,” while at the same time, the port of Massawa boasted the most extensive harbor facilities between Alexandria and Cape Town. Other Eritrean cities also reflected progress and industrialization. Tessenei was a hub for transportation and economic activity, while Dekemhare, about 40 km south of Asmara, was referred to as “zona industria” and “secondo Milano” and was full of busy factories and industries.

Critically, the period of Italian colonial rule also forged the basis of an Eritrean state and created its modern territorial boundaries, while contributing to the formation and development of a common, shared social history and unique national identity.

British occupation and post-war betrayal

In April 1941, after the decisive British-led victory at the Battle of Keren, Eritrea was placed under British Military Administration (BMA). Despite British promises of independence in return for assistance against Italian forces, these were quickly abandoned. British propaganda even promised, “Eritreans! You deserve to have a flag! This is the honourable life for the Eritrean: to have the guts to call his people a Nation.” These assurances proved hollow.

Instead, the British plundered Eritrea’s industrial assets and infrastructure, selling them off for profit. Sylvia Pankhurst condemned this exploitation as “a disgrace to British civilisation.” Meanwhile, the BMA sowed division among Eritrean communities, seeking to fragment the territory and portray it as too weak and divided to be viable as an independent state. They aimed to partition Eritrea between the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and imperial Ethiopia.

Federation by force

Ethiopia, too, portrayed Eritrea as economically dependent and politically fragile. In a 1947 speech to the UN, Aklilu Habtewold claimed Eritrea “could not live by itself.” The US echoed this narrative, fearing that an independent Eritrea might fall under Soviet influence during the Cold War. In reality, one of the main reasons the British, Ethiopians, and Americans worked so hard to portray Eritrea as weak and so heavily pressed their claims regarding the country was that it was full of development and considerable economic potential.

On September 20, 1949, the UN General Assembly dispatched a commission to assess Eritrea’s future. The delegation confirmed that the overwhelming majority of Eritreans favoured independence. Pakistani delegate Sir Zafrulla warned, “An independent Eritrea would obviously be better able to contribute to the maintenance of peace (and security) than an Eritrea federated with Ethiopia against the true wishes of the people. To deny the people of Eritrea their elementary right to independence would be to sow the seeds of discord and create a threat in that sensitive area of the Middle East.”

Nevertheless, on December 2, 1950, UN Resolution 390 (V) imposed a federation with Ethiopia, making Eritrea an autonomous unit under the Ethiopian Crown. Sponsored by the US, the resolution prioritized Cold War strategic interests over Eritrean self-determination. The American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles infamously declared:

“From the point of justice, the opinions of the Eritrean people must receive consideration. Nevertheless, the strategic interest of the United States in the Red Sea basin and considerations of security and world peace make it necessary that the country be linked with our ally, Ethiopia.”

Unlike other Italian colonies granted independence after World War II, Eritrea was denied its right to self-rule. Days later, Emperor Haile Selassie declared a national holiday celebrating the “restoration” of Eritrea. During a luncheon attended by the US Ambassador, the Emperor expressed gratitude for America’s decisive role in the UN decision.

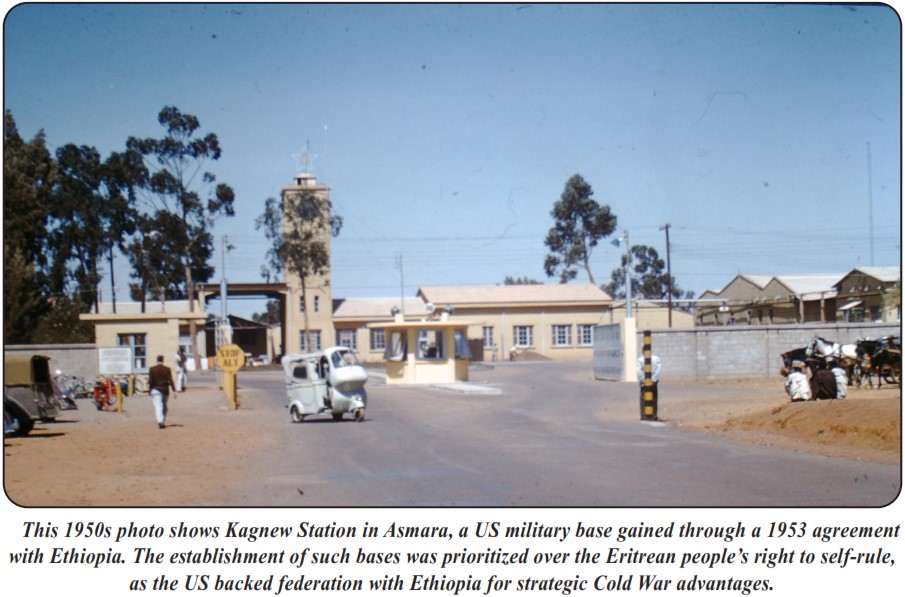

In return, the US gained key military advantages. On May 22, 1953, Ethiopia granted the Americans the right to establish military bases in Eritrea, including Kagnew Station in Asmara, which was then the world’s largest overseas spy facility. Subsequent agreements included comprehensive military aid and training for Ethiopian forces.

The UN-mandated federal arrangement granted Eritrea legislative, judicial, and executive autonomy in domestic affairs. But from the outset, Ethiopia treated it with contempt. The monarchy began systematically dismantling Eritrean autonomy, paving the way for annexation – actions that would eventually spark one of Africa’s longest wars of independence.

Situated in the volatile Horn of Africa and blessed with a long, pristine coastline along the Red Sea, Eritrea is a country marked by a rich, complex, and turbulent history due to successive occupation and aggression. After one of the longest and most destructive wars for liberation in modern African history, Eritrea finally achieved independence from Ethiopia in 1991.

A series that seeks to illuminate the country’s decades-long struggle against colonial occupation. While Part 1 explored the foundations of Eritrea’s colonial experience and early political aspirations, this instalment focuses on the systemic erosion of the “Federal Act” under Ethiopian rule and the pivotal events that gave rise to the armed liberation struggle.

Resilience amidst efforts to quash independence

On 2 December 1950, following a protracted international process, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 390(V) with a vote of 46 to 10. This resolution dashed Eritreans’ hopes for full independence, instead federating Eritrea with Ethiopia as “an autonomous unit … under the sovereignty of the Ethiopian Crown.” According to the resolution, Eritrea was to retain legislative, executive, and judicial autonomy in domestic matters, while Ethiopia would control defence, foreign affairs, and international trade.

However, Ethiopia’s absolute monarchy, under Emperor Haile Selassie, viewed the Federal Arrangement with disdain. This contempt was laid bare in a 22 March 1955 speech to the Eritrean Assembly by the Emperor’s representative, who declared:

“There are no internal or external affairs as far as the office of His Imperial Majesty’s representative is concerned, and there will be none in the future. The affairs of Eritrea concern Ethiopia as a whole and the Emperor.”

Over the following decade, Ethiopia systematically dismantled the Federal structure. Merely 19 days after the Federal Arrangement came into force, the regime issued Proclamation 130, placing Eritrea’s final Court of Appeal under the Ethiopian Supreme Court – an overt breach of the Eritrean Constitution. Eventually, the Eritrean Constitution was abolished altogether, the national flag replaced by Ethiopia’s, and Amharic was imposed as the official language, with Eritrean languages banned in schools and official transactions.

The Ethiopian regime resorted to additional draconian measures. Elected local leaders were forced to resign. Eritrea’s share of Customs revenues was confiscated, and foreign investors were pressured to divert investments to Ethiopia. Eritrean tax revenues served imperial interests, and profits from successful Eritrean industries were siphoned to the Ethiopian heartland.

Repression also intensified, while peaceful opposition was violently crushed. In 1957 and 1962, students in Eritrea staged mass demonstrations, and in February 1958, a four-day general strike by underground trade unions brought the country to a standstill. Ethiopian troops responded with lethal force, killing dozens, wounding many, and arresting hundreds. Prominent nationalist Eritrean leaders like Woldeab Woldemariam and Ibrahim Sultan were forced into exile, where they continued the resistance and helped form opposition movements.

Although Eritreans were promised the right to appeal to the UN in case of violations, repeated petitions by Eritrean leaders to protest Ethiopia’s actions were met with deafening silence. The UN and the international community failed to uphold their commitments. Ultimately, “Eritreans’ hopes and faith in the United Nations waned as the situation worsened.”

Finally, in November 1962, Emperor Haile Selassie formally dissolved the Eritrean Parliament by force and annexed the territory as Ethiopia’s 14th province. Western observers described the move as a “putsch” and “a brutal and arbitrary act.” Eritreans, dismayed and outraged, refused to participate in the regime’s staged celebrations.

As these events unfolded, the international community remained silent, time and again, despite the clear violation of Resolution 390A(V), which stated that only the UN General Assembly had the authority to alter the Federation. Rather than defeating the Eritrean national movement, this betrayal galvanized it. The imperial annexation became a turning point, spurring the transition from peaceful protest to armed struggle. Indeed, if Eritrea was denied the right of decolonization in the first place in the 1940s, the international community’s complicity by its silence when the bogus “Federal Act” was wilfully and utterly abrogated by the Ethiopian regime, nudged them to resort to armed struggle as the only option for regaining their inalienable national rights and human dignity.

The birth of armed resistance

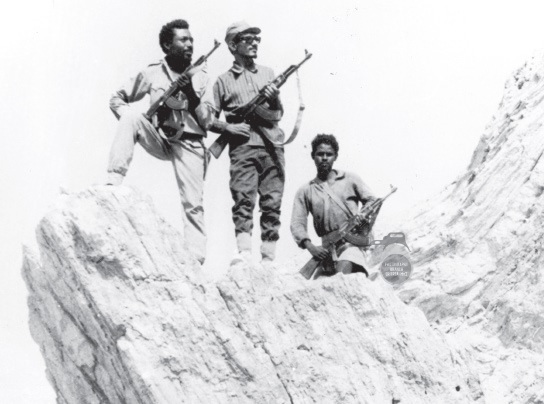

On 1 September 1961, Hamid Idris Awate, a seasoned soldier with a reputation among Italians, British, and Ethiopians as a rebel, fired the first shots of the armed struggle in the Gash Barka region. Leading a small band of fighters armed with a handful of aging rifles, Awate initiated what would become a 30-year war for independence.

Awate had earned medals for bravery during his time in the colonial army and was respected for his military acumen. A few months after the start of the armed resistance, Abdu Mohamed Fayed became the first martyr of the struggle when he was killed in Adal near Sawa. (Fayed’s grave is now in Sawa, and Awate died of illness roughly 10 months after launching the revolution.)

For the peace-loving Eritrean people, the armed revolution was “the expression of the indignation of a people whose rights [were] flagrantly and ruthlessly suppressed.” As one scholar succinctly put it, “Three times denied their dreams, the Eritreans now had no other recourse than to take their destiny into their own hands.”

This is the final installment in a three-part series illuminating Eritrea’s decades-long struggle for self-determination. the foundations of Eritrea’s colonial experience and early political aspirations, and the systematic erosion of Eritrean autonomy under Ethiopian rule and the events that ignited the armed struggle, the evolution of that struggle into a full-scale liberation war. It examines the immense odds Eritrean fighters faced, the global Cold War dynamics that shaped the battlefield, and the series of decisive victories that ultimately led to independence in 1991.

From spark to wildfire

On 1 September 1961, Hamid Idris Awate, a seasoned soldier once deemed a renegade by the Italians, British, and Ethiopians, and a small band of fighters armed with a handful of old rifles, fired the first shots of Eritrea’s armed struggle in the Gash Barka region. From these early hit-and-run skirmishes, the independence movement grew into a full-scale war for national liberation, engulfing the population like a wildfire.

Over the next three decades, Eritrea’s independence fighters – largely unsupported by the international community and facing fierce opposition from Cold War superpowers – battled successive Ethiopian regimes. These regimes were backed by extensive foreign military and diplomatic support from the United States and the Soviet Union (at different times, but sometimes simultaneously), and others, including Israel, Cuba, East Germany, Libya, and Yemen.

Initially, the United States provided Haile Selassie’s imperial regime with significant aid. Alongside the Americans, Israel established a military pact with Ethiopia, deploying intelligence personnel, high-level advisors, and elite training teams. Ethiopia’s military, thus fortified, still failed to contain the rapidly growing Eritrean resistance, which had transformed from a small group of “bandits” into a formidable liberation army.

From empire to junta

By 1973, the combination of famine, rebellion in the Ogaden, and mounting pressure from Eritrean forces led to unrest within Ethiopia. In 1974, the Provisional Military Administrative Council, or Dergue, led by Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam, overthrew the monarchy. Mengistu later realigned the country with the Soviet Union. Despite this shift, US and Israeli support continued for a time, underlining the geopolitical complexity of the Horn of Africa.

By late 1977, Eritrean forces had liberated most of the countryside and laid siege to key cities, including Massawa and Asmara. Meanwhile, Ethiopia faced war on a second front with Somalia over the Ogaden. The USSR responded decisively, dispatching military advisers and billions in arms. This was further bolstered by the deployment of thousands of Cuban, and South Yemeni troops. The intervention helped Ethiopia repel Somalia and reassert control, allowing it to refocus on Eritrea with renewed strength. This not only helped Ethiopia to prevail in the war with Somalia, but it crucially also allowed it to shift its military attention and focus more directly on Eritrea, all the while continuing to receive multidimensional support and reinforcements from its external backers.

Nakfa and the years of stalemate

Forced into retreat, the EPLF (Eritrean People’s Liberation Front) regrouped in the mountainous Sahel region, making Nakfa its military and symbolic stronghold. Between 1978 and 1981, Ethiopia launched five major offensives to capture Nakfa, all of which failed. In 1982, Mengistu launched Operation Red Star, deploying over 136,000 troops. Despite overwhelming numbers and Soviet backing, the operation failed, costing Ethiopia tens of thousands of lives and further damaging morale.

Following these failures, the EPLF steadily regained the initiative. A turning point came in March 1988 at the Battle of Afabet, Ethiopia’s regional headquarters. Often likened to El Alamein and Dien Bien Phu, it was Africa’s largest battle since WWII and resulted in a crushing Ethiopian defeat.

The tide turns

In February 1990, the EPLF launched Operation Fenkil, a meticulously planned and coordinated land and sea assault to liberate the strategic port city of Massawa. This operation severed Ethiopia’s military supply line through Massawa and led to massive Ethiopian losses – nearly 10,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or captured. It also signalled that Eritrean independence was no longer a distant dream but an imminent reality.

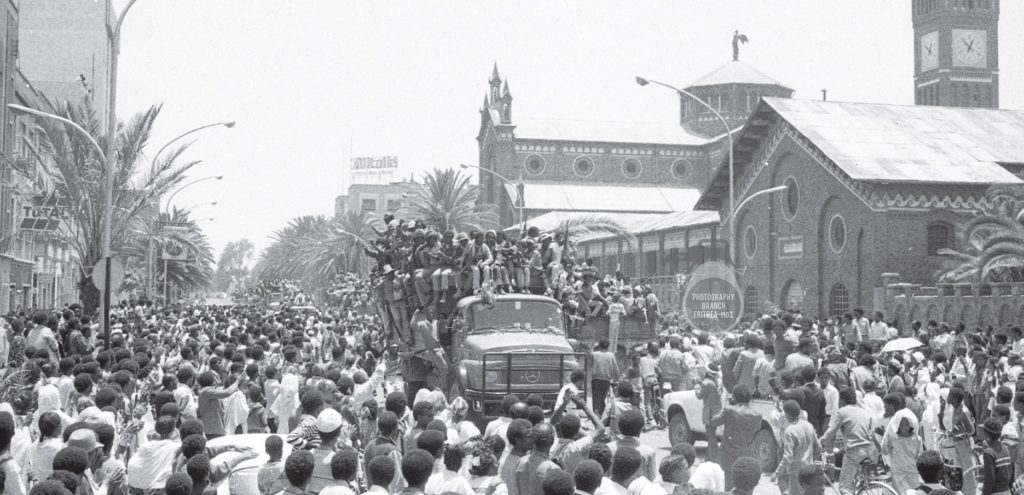

With Massawa secured, only Asmara and Assab remained under Ethiopian control. In May 1991, the EPLF defeated Ethiopian forces at Dekemhare, swept through surrounding towns, and liberated Asmara on 24 May. Assab fell the following day. Thousands of demoralized Ethiopian soldiers, who had comprised what many had for decades believed to be the continent’s best-trained and best-equipped fighting force, surrendered; (Mengistu had fled into exile in Zimbabwe few days earlier, on 21 May 1991).

As they triumphantly entered the capital, Eritrean freedom fighters were received by a rapturous welcome and scenes of sheer jubilation. After one of the longest and loneliest national wars for liberation in modern African history and following tens of thousands of deaths, numerous more injuries, and much devastation and destruction, Eritrea had defeated Africa’s largest, best-equipped army and finally won its freedom.

From liberation to recognition

Shortly after the EPLF victoriously rolled into Asmara in 1991, preparations were begun to conduct an internationally supervised referendum as the final diplomatic thread in Eritrea’s long and arduous struggle to assert its inalienable right of decolonization. On 29 May, Isaias Afwerki, then Secretary-General of the EPLF, called upon the UN to, “shoulder its moral responsibilities [to help conduct a free and fair referendum on Eritrea’s self-determination] without further delay”.

Two years later, in 1993, Eritrea was formally welcomed into the international community of nations as Africa’s 52nd nation-state following an internationally monitored referendum in which more than one million Eritreans from inside the nation and across the world overwhelmingly voted in favor of independence. Monitored by the UN, the OAU, the Arab League, and representatives from over a dozen countries, the referendum saw a staggering 98.5 percent voter turnout, with 99.81 percent of voters opting for independence.

Eritreans fought, endured, and triumphed

Eritrea’s path to independence stands as one of the most determined and resilient liberation movements of the 20th century. Against overwhelming odds and the indifference of the global community, Eritreans fought, endured, and triumphed. Their victory was not merely the toppling of an occupationist regime but the fulfillment of a collective dream long dismissed as impossible.

The legacy of Eritrea’s liberation war continues to shape its national identity. It serves as a stark reminder of the costs of freedom and the enduring power of a people united in pursuit of justice and sovereignty.